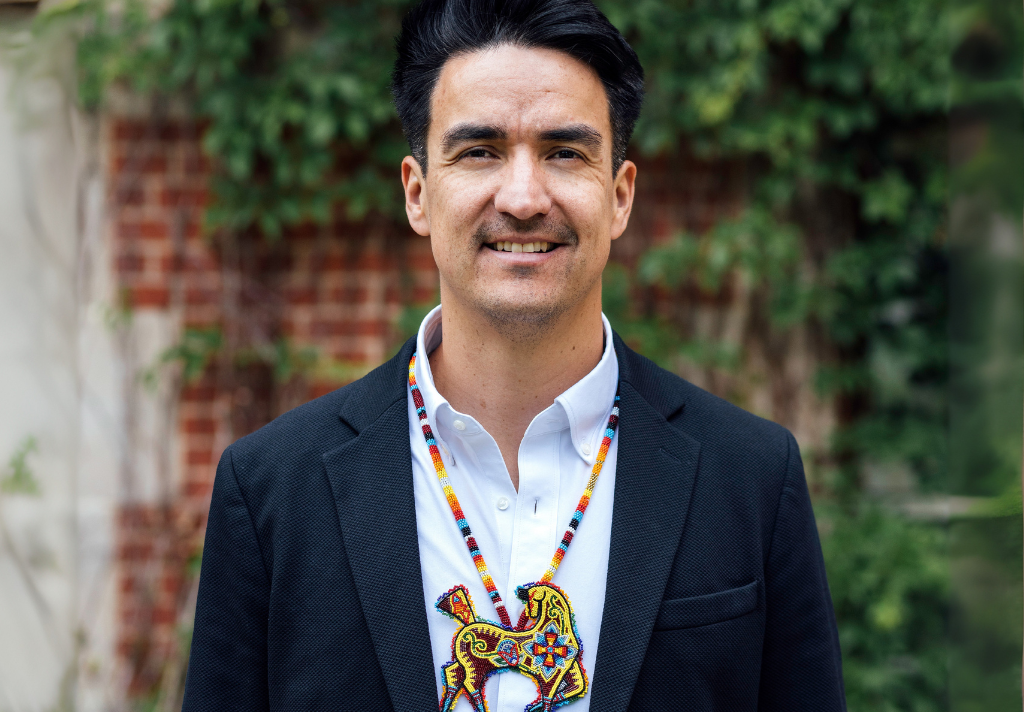

When Grant Bruno delivers his keynote at McGill University December 3 to mark the 2025 International Day of Persons with Disabilities, he’ll be inviting the audience to imagine a different way of understanding neurodiversity, one grounded not in deficits, but in belonging.

Bruno will draw on his experience as a parent of Autistic children and his research rooted in nêhiyaw (Plains Cree) knowledge to explore how Indigenous worldviews can reshape how we support neurodivergent children.

From diagnosis to relationships

For Bruno, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Alberta and member of Samson Cree Nation, the difference between Western and Indigenous approaches to neurodiversity begins with how each defines the child.

“In the Western system, you’re trained to look for deficits,” he said. “You’re trained to find what’s wrong.” The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, he notes, uses clinical language framing autism as a problem to be fixed.

“Our Indigenous way is to look at what’s right with that child. We still acknowledge challenges, but we focus on their gifts. How can we celebrate them in the way they deserve?”

Bruno’s work weaves Western frameworks and nêhiyaw knowledge systems to create culturally responsive care. As Academic Lead for Indigenous Child Health at the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute in Edmonton, and through initiatives like the Indigenous Caregiving Collective, he leads community-driven projects honouring children’s strengths while addressing systemic barriers.

Practical efforts include the creation of a “sensory tipi,” a calm, inclusive space at powwows and community events for children with neurodevelopmental differences. Families reported that cultural spaces like ceremonies were far less overwhelming for their neurodivergent children than were schools or grocery stores.

“Families felt safe,” Bruno said. “They described cultural events as inclusive and supportive. That’s evidence we can build on.”

Healing through inclusion and belonging

Bruno believes healing and support are deeply relational. His research and community work challenge the idea that support should be standardized or detached.

“I see children as part of a larger system, connected to family, community, school,” he said.

His PhD research with caregivers of autistic children in First Nations communities, including Six Nations of the Grand River and Maskwacîs, reinforced this approach. By sharing his own experiences and simply listening, he saw how isolating caregiving can be and how much trust matters. Strong relationships can later encourage families to share insights that benefit communities across Canada.

This relational lens extends into healthcare and education. Culturally responsive care helps Indigenous families see themselves reflected in institutions, he said.

“Even having Indigenous staff at a clinic – a receptionist, a nurse, a physician – can make families feel like they belong,” Bruno said. Allowing traditional practices, such as smudging in hospitals, also helps families feel welcome.

But systemic barriers persist. Jurisdictional divides between federal and provincial systems often leave children without support. Most disability and health services are provincial, while families on reserve fall under federal responsibility. Children just kilometres apart can have entirely different access to care.

“It’s unfair,” Bruno said. “Some Indigenous families have to uproot themselves and lose kinship supports just to get basic services.”

These divides create confusion about funding and follow-up.

“Families can wait years for a diagnosis before getting help,” he said. “Early intervention changes everything, for the child, the family, even the economy. We need systems that don’t make families wait years before they can access support.”

A hopeful vision for the future

Despite the challenges, Bruno remains optimistic: “I’m inherently hopeful. I know families, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, are doing incredible work with their children every day. That gives me hope.”

He is encouraged by the growing number of people outside Indigenous communities embracing similar approaches.

“It’s not just an Indigenous idea to see the beauty in our children,” he said. “Many cultures share that. My goal is to make sure the teachings I’ve been gifted, which I don’t own, reach the people who need them.”

For Bruno, decolonizing understandings of neurodiversity isn’t only about changing systems, it’s about restoring connection.

“For me, relationships come before the work. I take the teachings I’ve been given by Elders and from ceremony and apply them to my work,” he said. “The work naturally becomes relational, because at the heart of Cree worldview, and really at the heart of who we are as people, are the relationships we build and maintain.”

McGill’s 2025 International Day of Persons with Disabilities programming is organized by the Equity Team in the Office of the Provost and Executive Vice-President (Academic), in partnership with the Office of Indigenous Initiatives and the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, with support from Communications and Institutional Relations and the Desautels Faculty of Management.

A special screening of “They Are Sacred” and dialogue organized by the Office of Indigenous Initiatives, the Transforming Autism Care Consortium (TACC), and CanNRT also took place at The Neuro on December 3, offering space for reflection and conversation connected to these themes.